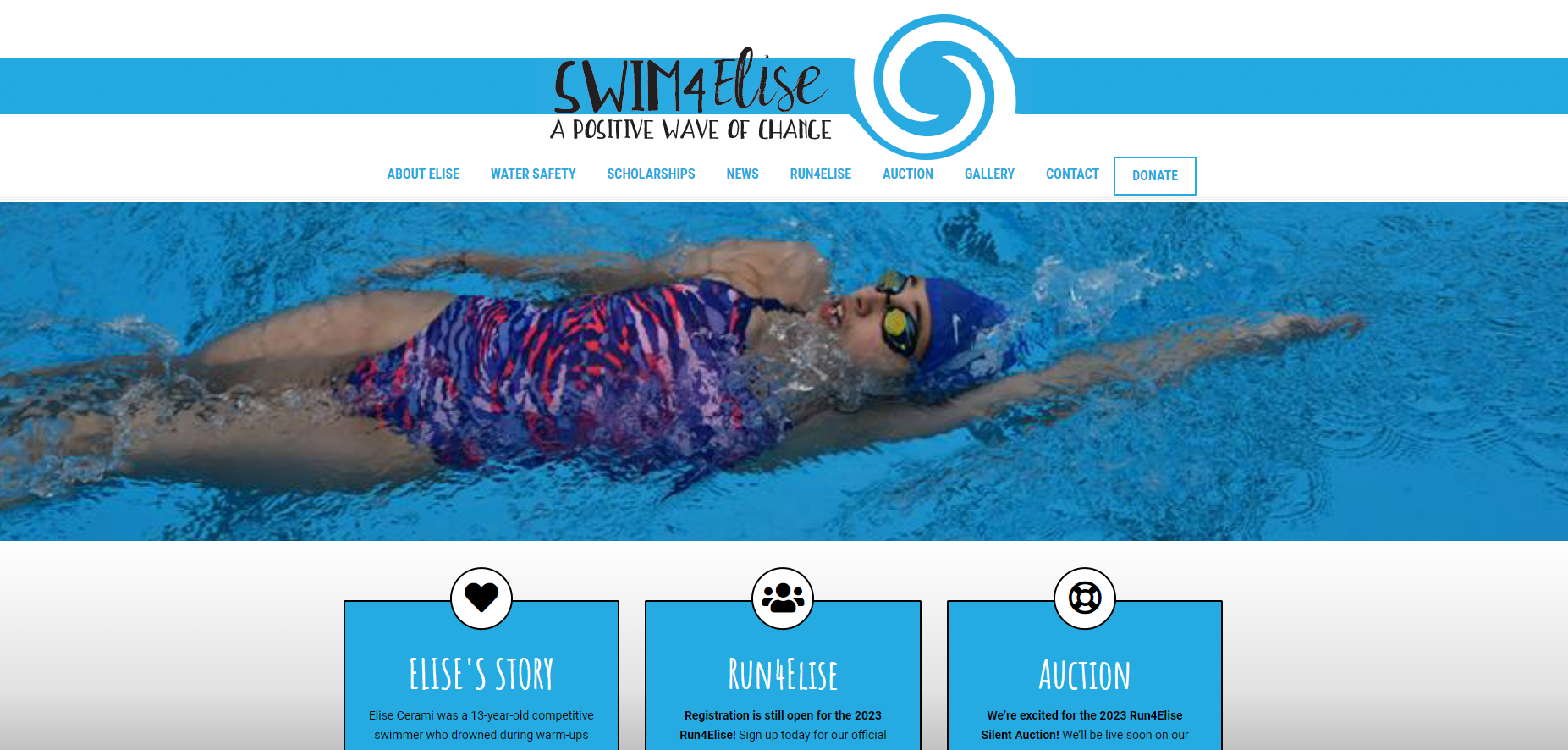

Chuck was our lead guide for the day, and he was telling us what to do if we fell out of the raft. Don’t try to stand up (he’s known someone who died from having a foot trapped between two toothy, jagged rocks). Don’t swim toward any wood piles or strainers (you could faceplant or snap your neck).

Swim toward the raft, he said. Be aggressive.

You own the river.

I looked over at nine-year-old Emma, who was sitting next to me on the old school bus—our transportation from the raft shop to the river drop point—and saw the tears forming in her eyes when she realized he was serious.

Never mind that he started our little discussion by telling us there was no reason to be afraid. Never mind that he said he was only required by law to give us these warnings.

Chuck had a wild look in his eyes, like he had seen things, experienced things, that humans shouldn’t have to endure. Emma started to cry, and as I peeked over my shoulder to face my husband, in the row behind us, I came within seconds of scrapping the whole adventure.

You know, for Emma’s sake.

Matthew had an arm around Lissa, who looked confused. At the age of seven, she understood words like “death” and “falling out,” but at a more esoteric level. Mostly it was Chuck’s tone that gave her pause. His gesturing hands and hoarse yell were telling her this might be more than just another ride at Six Flags.

I was grateful we'd left our four-year-old son back in Breckenridge with his grandmother.

“You’ll be fine,” I whispered, to myself as much to my girls. “You heard him. Nothing to be nervous about. He’s not trying to scare you.”

Still, my inner monologue scoffed. WTF is wrong with this man? Does he not know anything about children?

I forced a smile. Wiped a tear from Emma’s cheek. Thought to myself there’s no way they would let us go out there if we weren’t going to be safe.

The problem was, I had these two thoughts buzzing through my head, like mosquitos you want to smack but can't quite see.

I’d been rafting exactly three times in my life. And each time, EVERY time, I had been the one to fall out. In my memory, falling out was annoying. Maybe cold. Startling. But it never felt like I was dancing with death under the river, the way Chuck made it sound. And yet history would surely repeat itself. I would go overboard again like an idiot, this time in front of my kids and husband, so I’d have to summon back all this safety stuff he was covering like a rapid-fire sportscaster on ESPN. I could barely remember my own name at this point, let alone remember what he said about how to get out from under the raft if you should happen to surface in an unfortunate location.

And there were, it seems, many unfortunate locations.

The other thought I couldn’t ditch was on everyone’s mind, and Chuck wouldn’t let us forget it. We were dealing with record late-season snowfall, snow melt, and rain. The Arkansas River was twice as high as its normal, exhilarating self. The flow rate was pure insanity for us beginners at almost 2,200 cubic feet per second. That’s about 135,000 pounds of water pushing down on you every second.

Chuck wanted us to get the significance of this pressure.

IMAGINE, he barked out, that someone is throwing a BASKETBALL at you!

He then went on to describe how the force of the current river, swollen with the season’s drainage, would feel like someone throwing 135,000 basketballs at you simultaneously. In your face, up your nose, into your head.

Well, shit.

This was the moment when I had to man up. Be the Mean Mom. Make that tough decision. I knew that our friends in the row ahead of me were all smiles and bravado, but they weren't staring at two terrified cherubs like I was. I had to put a stop to this ridiculous idea. We couldn't possibly go rafting into some “Clash of the Titans” hellscape.

We were doomed.

We were dealing with record late-season snowfall, snow melt, and rain. The Arkansas River was twice as high as its normal, exhilarating self. The flow rate was pure insanity for us beginners at almost 2,200 cubic feet per second. That’s about 135,000 pounds of water pushing down on you every second.

But I couldn’t make myself form the words. Because I was being a complete and utter chicken, and I knew it. As I turned to check out the other passengers on our bus, I might have noted slight trepidation, but no one looked on the verge of a full-blown panic attack. I was being the moron Chuck mocked, the one who moaned about my life jacket being too tight.

Grow up, he had told us.

Fine. Alright then.

We were asked, at long last, to get off the steamy bus and get ready to board our raft. Our group’s guide, Will, seemed energetic and pleasant, but I knew him to be nothing more than a young, inexperienced sailor steering us into certain chaos. He, too, tried to give us some safety instructions, plus guidance on how to actually help paddle the vessel—very important if we were to all stay afloat when we hit the rapids—but I was too busy struggling with frightened kids worn from the heat and frustrated by splash jackets that didn’t want to go over heads. I gave up.

Fast forward five minutes. We were drifting in the drink, so to speak, all six of our crew plus Will, trying to find positions of safety and comfort, while practicing our “forward one” and “forward two” commands. I was trapped. We were moving, the course was set, we were motor-less and motion-full.

And throughout those first agonizing moments where I sat poised and ready to yell I CANNOT DO THIS, I kept checking on my girls, who seemed to be growing more and more at ease with each passing second. My husband was fine. He was up front, helping to take the waves head-on, and I had no choice but to smile like a rodeo clown, willing to be gored for the show of it all, for the applause.

I wish I could explain how exactly it was that I calmed myself down. I think so much of it had to do with seeing my children expand before my eyes, their confidence inflating like balloons attached to faucets, unable to stop from overflowing, close to bursting. They ceased to be afraid the moment we sat on the boat, I think. Maybe because they didn’t exactly understand the gravity of what could happen, but maybe because they did—and they just got over it. Emma paddled with us for at least 45 minutes, in sync with our commands, balancing herself like a pro. Lissa wore a grin the size of the state of Colorado itself, and with the exception of getting chilly towards the end of our expedition, that grin never left her face.

I became entranced just by watching the water. I remembered how, when driving in snow, you could almost watch a single snowflake descend from the sky to the windshield, and it slowed the process down—made it more manageable. I began to see how each wave was distinguishable as it rose to the hull of the raft. I tracked them one at a time, each crest and trough, steeling my hips and thighs to carry the toss from side to side.

I will not fall out of this raft, I kept repeating. You cannot make me.

At the most hectic of moments, the most ridiculous-looking gigantic rapid—a class IV lovingly called Seidel’s Suck Hole—I almost lost it. I saw the magnitude before me, and I shouted to my children to hold on, even as I tried to maintain my composure, hands on the paddle, ready to help my boat-mates. Oh, my heavens, if I could just convey to you how it feels to have your vision completely obscured for one incredibly long second, fighting off the invisibility of the world to open your eyes and verify The Only Thing That Matters In the World: I still had two kids on the boat. Two open-mouthed, ecstatic kids who couldn’t have looked happier if Santa himself had just plopped onto the raft with a bag full of toys.

They ceased to be afraid the moment we sat on the boat, I think. Maybe because they didn’t exactly understand the gravity of what could happen, but maybe because they did—and they just got over it.

Altogether, we spent about five hours traveling through Brown’s Canyon that day. When we were headed into the last stretch, Will called Emma to come take the rear with him and give us our commands to get to shore. She briefly hesitated, wondering if she was supposed to say yes, but when we nodded, she was off. Literally buoyant.

“FORWARD TWO!” she insisted. “FORWARD! FORWARD!”

We careered toward the bank, nudged the sandy shore, came to rest. Will gave Lissa the important task of watching the raft while he took our equipment back up to the vans that awaited us. She sat like a hawk, holding the tow rope, in awe of being given such responsibility.

As we rode the cramped bus back to the shop, all of us tired and wet and carrying sand in places where sand should never go, I tried to process what had just transpired. How I had gone from a blithering coward, to a put-off mom insistent on saving her children, to a simple person watching simple enjoyment launch itself from the unlikeliest of undercurrents… it was too much.

I sat back, resting my hand atop my husband’s forearm. The wind buckled in through the open windows, threatening to steal my visor. I felt, for the first time in so many years, that I could change. That the power of the world around me could give me power. That I could learn again. What an open book I have before me. What gratitude I want to share. Oh, the things I owe my children.